I’ve been thinking that we’ve all been misled.

A chat at work about brassicas being heavy feeders led me thinking ….

The whole of agriculture and horticulture has accepted without question that soils with high fertility are not only a good thing, but are one of the main things to aim for – in organic, biodynamic, regenerative and chemical-based systems.

Muck spreading in SW England

High fertility often leads to big yields of whatever crop you’re growing, so it must be good, right? Many annual, forage, shrub and tree crops only give the yields expected nowadays when there are excessive amounts of nitrogen and potassium applied to the soil. And the undervaluing (in the UK and many other countries) of food and the growers who produce it means that they feel the need to maximise yields.

So what’s the problem?

There are serious downsides to managing for high fertility. A major one is that excessive nitrogen applied to and circulating in the soil – whether applied as manures or chemical fertilisers – leads to lots of it escaping. Yes, some is taken up by the crop. But a lot – in the region of 80-87 % of chemical-based nitrogen, and 50% of manure-based nitrogen – is lost from the soil through a mix of washing out of the soil thereby polluting groundwater, and being lost into the atmosphere through oxidation into oxides of nitrogen. These latter compounds, as you probably know, are very powerful greenhouse gases – 290 times more powerful than carbon dioxide. This, more than anything, is what makes most high-fertility growing unsustainable in my view.

There are other downsides too. Plants respond to high fertility by putting on new growth with extra high nitrogen content, which attracts pests, and which is more susceptible to fungal diseases. So this leads to extra management needed for pest and disease control – extra chemicals used in most of agriculture.

The high nitrogen is also very detrimental to mycorrhizal fungi. These vital members of the soil community hate excessive nutrients and often fade away in their presence (they also hate compacted soils so become even rarer in chemical-based agriculture). Without them and the benefits they bring, the crop plants become even more vulnerable – to soil-borne pests, to drought and other stressful situations. And this leads to even more management interventions required – more chemicals, more irrigation.

Nematodes can cause root and crop damage but are controlled by mycorrhizal fungi

We need to remember that high fertility is a fairly rare and occasional event in nature, usually after a major event leading to a forest fire or a flood, where a pulse of high fertility is created by ashes, river silt etc. Ecologically this kick-starts natural succession with annuals as the first plants to recolonise bare soil. The annuals quickly use up the excess nutrients and then perennials take over in the lower-nutrient regime. Traditional swidden agroforestry emulated this by cutting down a small bit of forest, burning the woody material, then growing annuals for a few years followed by a food forest system: these systems in the topics were highly sustainable while the human population was low.

There is a tendency for organic and regenerative growers to believe that nitrogen from animal sources is less damaging to the environment, and to some degree they are right – at least the nitrogen from manures is not made in energy-intensive factories like chemical nitrogen fertilisers, and less of the nitrogen is wasted – only 50%(!) But that is still a lot of nitrogen potentially damaging the environment. Not to mention the methane from ruminants but that’s a whole other issue.

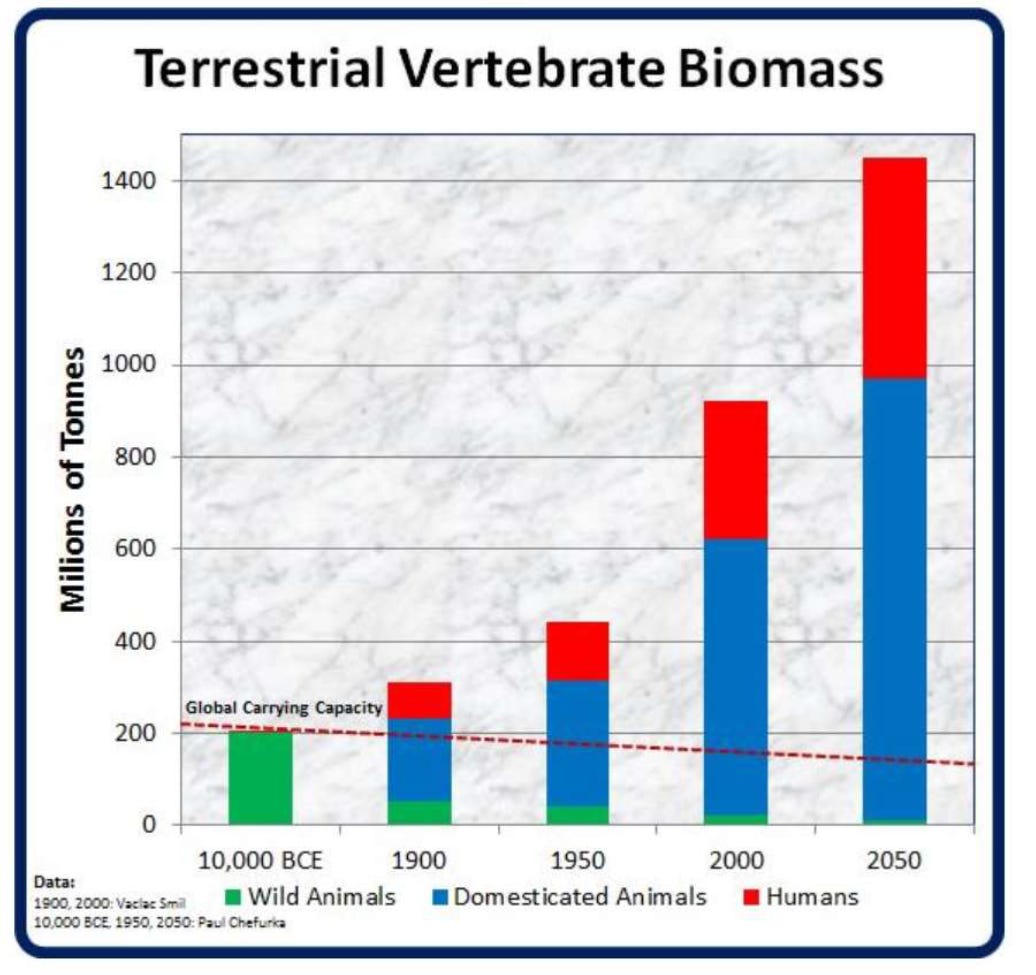

How much less nitrogen should there be in our growing systems? It’s difficult to give any sort of accurate figure. The problem for non-organic growers, especially arable growers, is that the soil has been damaged so much that it has no resilience left and without plentiful fertiliser crops can completely fail (although the cost of nitrogen fertilisers has risen hugely since the Ukraine war, encouraging farmers to cut down a bit.) As for animal-based agriculture, with livestock and their manures, it is instructive to look at the work of the renowned population biologist Prof. Vaclav Smil. His work shows that to stay within ecological carrying capacities there would need to be perhaps 10% or less of the livestock that there are now (and a lot fewer humans but that’s a whole other discussion.)

Graph showing mass of terrestrial vertebrate biomass and global carrying capacity (the maximum population size of a biological species that can be sustained by that specific environment, given the food, habitat, water, and other resources available.) Source: Smil (2011).

Some people will say: “we’ve got to maximise yields otherwise there won’t be enough food for everybody”. My response to that is that without a sustainable agriculture there is no future for a large portion of the human population; if the causes of climate change are not tackled in every area – including agriculture – then an even larger proportion of the human population is endangered.

By emulating natural ecosystems, food forests operate on a moderate fertility regime, though sometimes they are established starting with annuals in high-fertility and going through a succession process. Nitrogen-fixing plants in them are self-regulating, fixing less nitrogen when there is enough in the system already. This means that a healthy mycorrhizal layer supports and benefits all the plants within them. Drought resistance comes naturally. And the layered cropping system means that although the yields of individual crops may be less than those of a monoculture of that crop grown intensively, the total yields of the layered crops can compensate for the loss.

Perhaps we need to rethink our expectations of what are sustainable yields. It’s not easy, after being told that we should get x kg of crop with high-fertility growing, to accept that two thirds (or whatever) of that is just fine. But in a way it’s not different than accepting that we all need to reduce our high-consumption lifestyles and realise that having enough rather than always wanting more is essential to the future of human civilisation.

Reference: Smil, V. 2011. Harvesting the Biosphere: The Human Impact. Population and Development Review 37(4) : 613–636.

http://vaclavsmil.com/wp-content/uploads/PDR37-4.Smil_.pgs613-636.pdf

Thank you for that post, it resonates deeply with me! We have always worked toward that goal and so far (about 10 years in) I can say it's working OK - a mixed vegetable/fruit backyard garden with no imported fertility and 0 synthetic chemicals.

But in order to do that, we set a realistic expectation from the get go. We don't expect to get truckloads of produce, but everything we get is a fully fruit of our land.

So interested to hear about Swidden agroforestry - would love to weave that kind of process oriented approach into community gardening